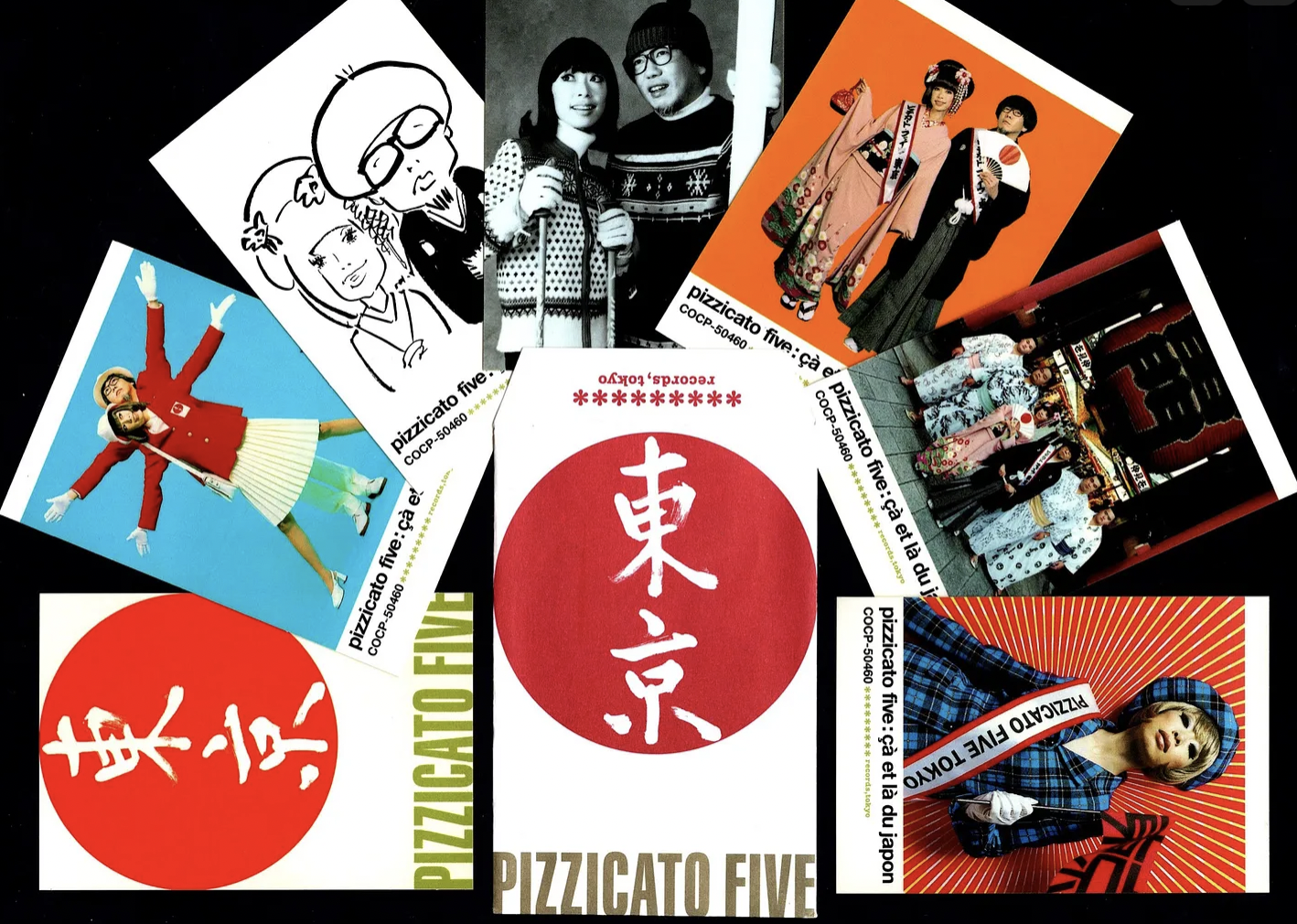

Photo Courtesy of City Game Pop

TOKYO — Following the emotional “hangover” of the 5th Anniversary, the release of the 78-track soundtrack for ‘Once Upon a Katamari’ has provided a sudden, cross-generational validation for one of J-Pop’s most maligned chapters. The score acts as a “missing link,” redeeming the 2001 final studio album from Pizzicato Five, Çà et là du Japon—a record long dismissed by Western critics as a commercial and aesthetic failure.

The soundtrack represents a definitive proof of concept for the Shibuya-kei aesthetic. By uniting pioneers like Clémentine and Shigeru Matsuzaki with the modern vanguard of DAOKO, chelmico, and Etsuko Yakushimaru, the score proves that the “Japan-as-Theme-Park” concept was not a joke, but a prophetic blueprint for modern cultural identity.

The Conflict of “Authenticity”

Historically, Western analysis of the Shibuya-kei movement has been characterized by a specific critical bias. For a decade, critics championed leader Konishi Yasuharu as long as his work functioned as a mirror for European sophistication, sampling French yé-yé and Italian soul. The band was celebrated globally as long as it remained “stateless.”

The divorce occurred when P5 turned the ironic lens toward Japan itself. By sampling the Kimigayo (the national anthem), traditional Bon Odori, and even a Pokémon theme, P5 created an “indigestible” mix of the sacred and the commercial. This led to a visceral rejection by the critical vanguard; most notably, W. David Marx famously handed the album a “D,” labeling it an “Orientalist failure” and comparing it to a “tacky provincial gift shop poster.”

A Legacy of Cultural Puzzles

The Katamari series has served as a hall of fame for this aesthetic, featuring indietronica figures like Rei Harakami and Buffalo Daughter, as well as the genre’s definitive muses, Kahimi Karie and Maki Nomiya. The recent soundtrack deepens this connection by featuring Saya Asakura, blending traditional enka singing with modern production—a direct continuation of the “tourism performative” style Konishi explored in 2001.

This approach treats culture as a brilliant puzzle of collectible objects. By acting as “performative tourists” in their own city—symbolized by P5 posing in Western mod attire in front of the traditional Kabuki-za theater—the band broke the cage of “authenticity” built by outsiders.

From Failure to Pop Art

The success of the Katamari ecosystem suggests that Western critics historically confused cultural reclamation with a “joke.” What was dismissed as “corny” in 2001 was, in fact, Pop Art. Twenty-five years later, the “innoble end” of the band is being re-read as the birth of the “Japan Cool” era, proving that local everyday life and traditional imagery could be just as sophisticated as the international records the band once imitated.