Photographer Jason Renaud | Credit: Nylon

Los Angeles, CA – September 29, 2025 – The notion of the “mean girl” is a cultural paradox—someone society loves to ridicule yet can’t look away from, a figure we hate and adore in equal measure. Slovak pop star Adéla Jergová has seized that tension, reclaiming the title for herself and flipping it into a critique of how the music industry portrays women. Her debut EP, The Provocateur, is part satire, part manifesto, and all pop spectacle.

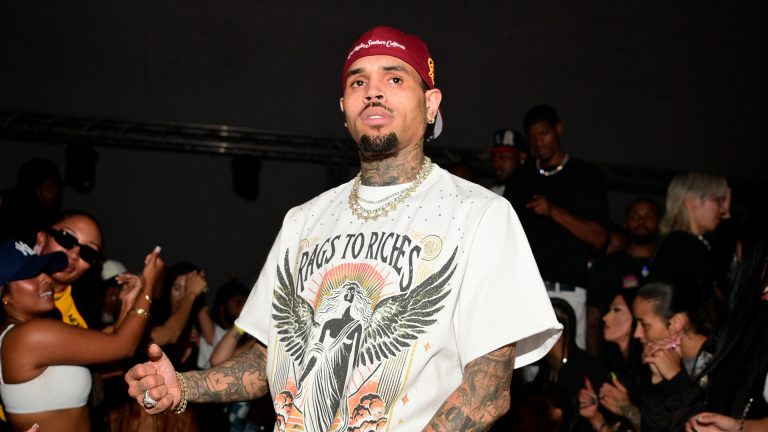

The world was first introduced to Adéla on Netflix’s reality competition show Pop Star Academy, which followed twenty young women as they trained under an intense K-pop system to form the global girl group Katseye. Adéla quickly emerged as a frontrunner due to her incredible dance skills, commanding vocals, and sharp stage presence. Yet despite her momentum, she was ultimately eliminated due to low fan votes and the judges’ belief that she seemed more suited to being a solo artist—a prediction that would prove uncannily accurate.

Pop Star Academy quickly built a devoted fanbase after premiering on Netflix in 2024, with viewers eager to champion their favorites—and just as eager to tear others down. Adéla emerged as one of the show’s most polarizing contestants, thanks to her willingness to confront conflict head-on and call out what she saw as unfair. Her outspokenness earned her the label of “mean girl” by the Dream Academy fandom. However, instead of resisting the label, Adéla leaned into it, harnessing her reality-TV “villain ”reputation to her advantage and positioning herself as one of pop’s boldest new voices.

Adéla turned the notoriety from Pop Star Academy into fuel for her solo career. In late 2024, she independently released two singles, HOMEWRECKED and Superscar, which created enough buzz to earn her a Capitol Records deal. In August of this year, she dropped her debut EP, The Provocateur, and has already amassed over 1 million monthly Spotify listeners. Her music is both experimental and irresistibly catchy, blending dance-pop and electropop while drawing on the recent hyperpop craze.

Her meteoric rise was achieved in less than a year and is a masterclass in marketing in the digital age. Her art thrives on provocation: lyrics that push boundaries, choreography designed to shock, and an online presence that courts controversy as much as it critiques the spectacle of fame itself. That drive to shock and subvert reaches its peak on the EP’s cover art, which depicts Adéla in a concrete underpass, wearing a thong and black leather jacket, posed as if urinating like a man. The image may nod to visual artist Sophy Rickett’s provocative series Pissing Women, which challenged the cultural double standard of men urinating in public. Regardless, her cover perfectly sets the tone for an EP that is at once bold, subversive, funny, and unapologetic.

Turning Criticism Into Commentary

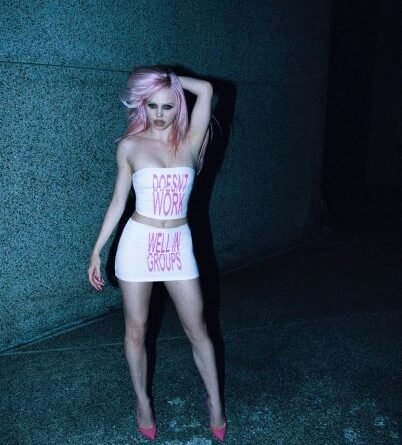

Adéla has crafted an online persona that feels unfiltered and mischievously self-aware—like a girl filming from her bedroom who just happens to know exactly how to stir conversation. On Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok, she embraces a raw, funny style that thrives on poking fun at herself and her haters. She’ll caption a clip of her dancing with, “Adela from Pop Star Academy is so mean and her song sucks,” or joke, “me when I woke up one day and the whole internet turned against me :).” Her branding follows the same mischievous streak. Her Spotify bio declares, “born to be solo xoxo,” a sly nod to her Pop Star Academy past, while her merch has the line: “Doesn’t work well in groups,” stamped on it in graphic hot pink letters.

That same tongue-in-cheek defiance runs through her music. In “Machine Girl”, her first single under Capitol Records, Adéla confronts her “mean girl” reputation head-on. Over a bed of heavy synths, Adéla sings in a high, distorted voice the refrain, “Mean girl, mean girl / Make-you-wanna-scream girl / Why you comin’ at me, baby? / Yell at the machine, girl.” The track flips the insult on its head, pointing out how women online are often attacked and ridiculed while the real culprit is the music industry “machine” profiting from pitting them against each other.

The music video for “Machine Girl” takes the critique a step further. Adéla and her dancers break out into a hard-hitting dance routine choreographed by Miguel Zárate, where Adéla’s razor-sharp moves and signature flexibility are on full display. The dance sequence eventually turns into a battle against another girl, their fighting builds in intensity until Grimes, credited as both a writer and producer on the track, steps into the frame, shouting “Cut,” and urges the performers to pour even more rage and vitriol into their fight. By pulling back the curtain to reveal that the spectacle was staged, Adéla highlights how easily audiences consume conflict that is, in truth, orchestrated—whether for a reality show like Pop Star Academy or by the media and entertainment industry at large.

In her cheekily titled track “FinallyApologizing”, Adéla takes direct aim at the misconceptions and judgments she faced after Dream Academy. Over a Euro-dance beat, she baits her critics by singing, “Sorry that my friends are all still friends with me / And that I’m not as bad as you want me to be / You only get to know me parasocially.” Then, as the song erupts into a wall of jagged buzzsaw synths, she chants the refrain: “You won’t get what you want from me.” Once again, Adéla uses criticism as the material for her music and comments on how fans and the media alike project narratives onto her while knowing little of the real person behind the image.

Sex, Pop, and Spectacle

Her latest single, “SexOnTheBeat”, takes aim at the industry’s oversexualization of women and pushes boundaries through her abrasive sexuality and bold choreography. The accompanying music video, directed by 91 Rules, opens with Adéla with pastel pink hair and bleached brows, performing exaggerated orgasmic gasps before a shrine-like mood board to pop culture, across which hot pink duct tape declares: sex = pop. The video then shows Adéla tuning into a mock “masterclass” led by Christina Aguilera, promising to “harness your sexuality to become pop royalty in eight weeks.” From there, Adéla dives into a set of deliberately exaggerated raunchy dance moves choreographed by Robbie Blue—contorting, humping, and thrusting with a brutalist awkwardness that reduces sex to something mechanical, almost absurd. Eventually Adéla is performing before a crowd in what looks like a museum gallery, and in the last shot she is shown—exhausted, smiling with a deranged gleam in her eye—before shoving the camera away.

What makes Adéla’s commentary about female sexuality being used as a marketing technique land, is Adéla’s knack for holding a mirror to pop culture’s ugliest clichés and reflecting them back with a wink. “SexOnTheBeat” isn’t just a reference to the “sex sells” mantra—it’s a reminder of how threadbare that logic has become. Her lyrics underscore the ugly, exploitative nature of over-sexualization in pop music: “Do My Dirty Dance Tonight / Serve It On A Silver Platter, Baby / Make You Think The Choice Is Mine.” By exaggerating the trope of “sex sells” to its breaking point, Adéla turns a tired industry cliché into a punchline, and in the process, reclaims the spectacle as her own.

Defining Her Own Pop Story

Adéla has all the makings of a conventional pop star: beauty, talent, sex appeal, but just beneath that polish is a darker, desperate, unhinged energy that makes her stand out. She cultivates a “broken Barbie doll” image: always shown in the splits, twisting her body into contortions, rolling across the floor with stringy hair, dark makeup, and a face caught somewhere between anguish and ecstasy. In her work, the glamour of pop collides with something jagged and messier, and the effect is impossible to look away from. Through her music and aesthetic, she exposes the darker currents of an industry that often leave artists exploited and powerless. For instance, In “Superscar” she says “Shut my lips to speak / Stick to your strategy / I know you like ’em weak / Sold you a piece of me.” Her approach to pop suggests an awareness of all the harsh realities of the industry and a desire to use that darkness as the raw material for her art.

Love her or hate her, Adéla refuses to leave anyone indifferent. Her work demands a reaction—bold, subjective, and unapologetically subversive. Whatever you think of her, it’s hard not to admire the audacious spirit and creativity behind her work. Her lyrics, visuals, and stage presence present something strange, eye-catching, and totally new in today’s media climate.