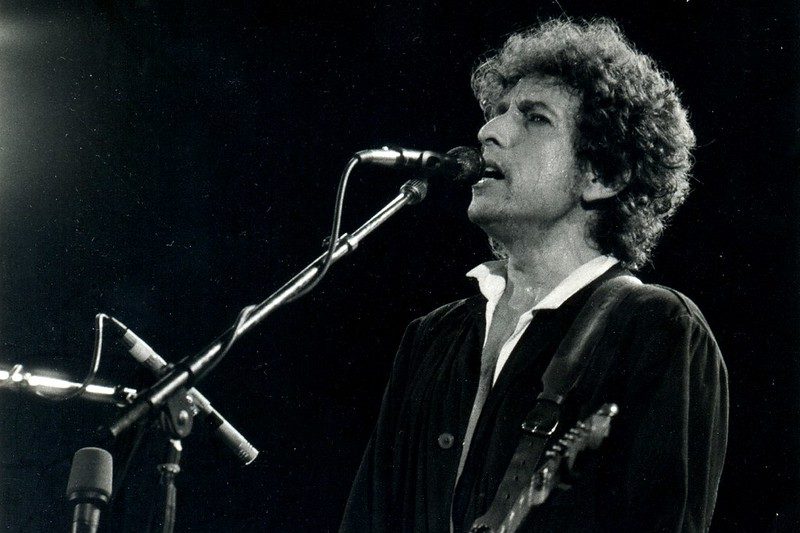

Photo Credit Xavier Badosa's | Licensed as CC BY 2.0

In 2016, Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for ‘having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition,’ a fitting honor for a musician whose words have long been treated as literature. For decades, critics and fans have poured over his work, but what happens when we ask a Large Language Model (LLM)—the same AI technology behind tools like ChatGPT—to sift through every word Dylan wrote between 1962 and 2012? A recent research project applied the power of Network Science and “Distant Reading,” a method championed by scholar Franco Moretti, to find out. The results offer the first-ever quantitative map of one of modern music’s most elusive minds.

The Unstoppable Rise of Metaphor

The AI analysis confirmed what many critics have sensed: Dylan’s writing steadily grows more oblique. The data, however, put a precise number on this shift. By charting the connections (or “edges”) between ideas in his songs, the LLM showed that the share of metaphorical expressions rose consistently across six decades. Where the 1960s saw a near balance, the percentage of metaphors continued to climb, crowding out plainspoken language. This long-term, gradual change, too subtle for the “naked eye” to track, provides hard evidence for Dylan’s growing complexity. Interestingly, the model also tagged these metaphorical expressions as often carrying a more negative emotional tone on average than his literal statements.

Quantifying the ‘Complete Unknown’

The study also provided numerical proof of Dylan’s famous “dishabituation”—the deliberate disruption of expectations that legal scholar Cass Sunstein noted keeps his audience engaged. By measuring how often a song mixes its most central, common themes with peripheral, unexpected imagery, the researchers created an index for unpredictability. This index spiked dramatically in the 1980s, a decade musicologists often call Dylan’s most wayward, when he veered from gospel rock to folk revival to synth-pop, creating a unique mesh where explicitly religious vocabulary linked directly to worldly political critique. This quantification of surprise validates the spirit of an artist who remains, as his own lyric suggests, ‘a complete unknown.’

The Macroscope for Modern Art

Ultimately, this analysis is not meant to replace the deeply personal act of close reading—after all, no algorithm can tell us why a song gives us chills. Instead, as digital humanities scholar Ted Underwood cautions, the AI acts as a ‘macroscope’—a tool that offers a fresh vantage point by visualizing vast data sets. By tracing the surge of protest themes in the 1960s, the introspective peak of love/romance in the 1970s, and the dark, reflective tone of the 1990s, the model provides an objective framework. It confirms theories, refutes folklore, and sparks new questions about how Dylan’s restless genius mirrored the cultural currents and his own life stages. It’s a powerful demonstration of how new quantitative tools can illuminate the rich, connected tapestry of great art.